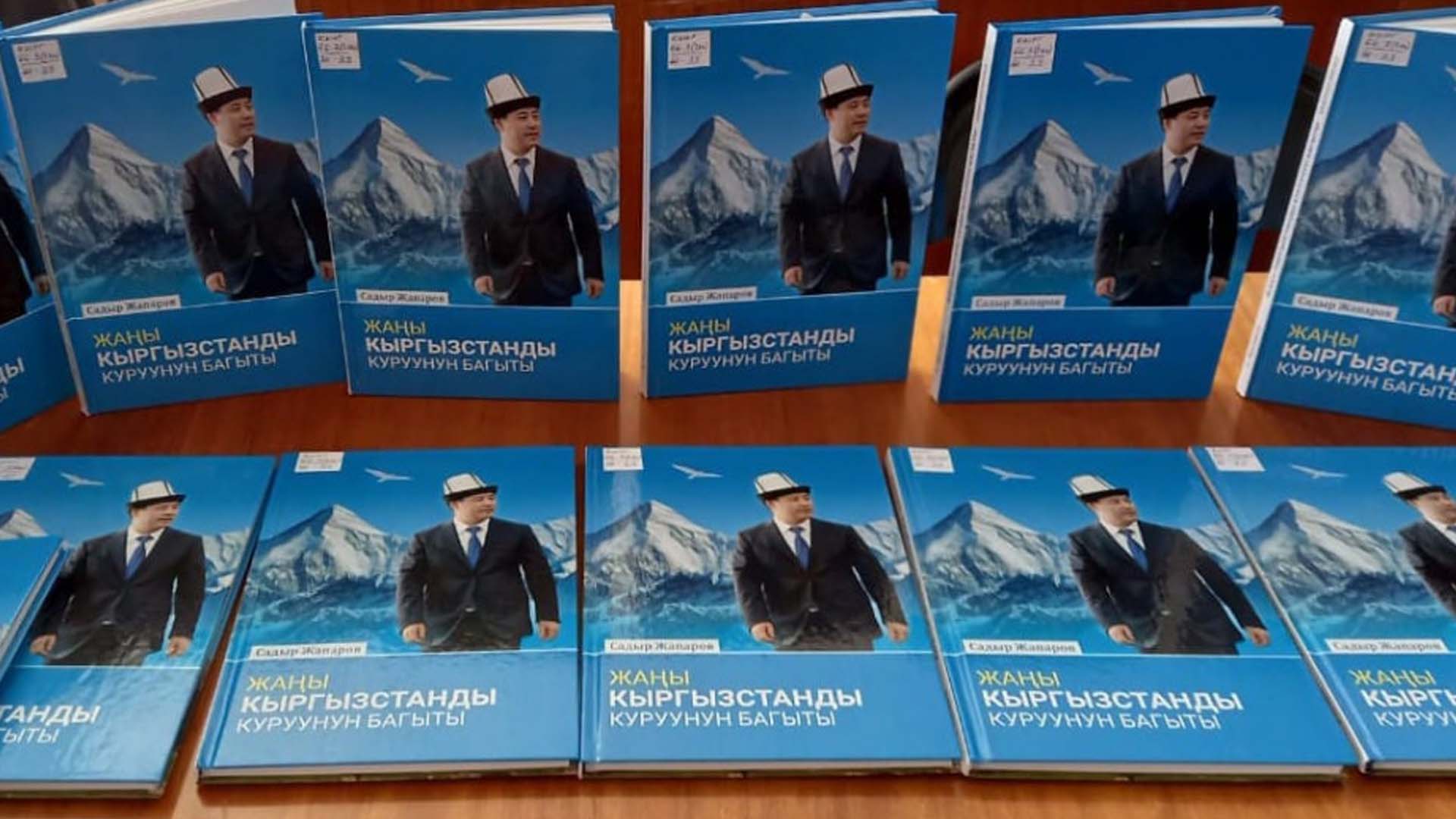

In 2023, the President of Kyrgyzstan Sadyr Japarov wrote and presented a new book with the title “The Path to Building a New Kyrgyzstan.” Thus, he joined his colleagues in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. But are the regimes of Central Asia really capable of changing?

The leaders of the Central Asian countries are loudly trumpeting new pages and chapters in history. And there are even heartfelt speeches about the creation of “new countries.” Thus, Shavkat Mirziyoyev in Uzbekistan created the slogan “New Uzbekistan” for his 2021 election campaign five years after coming to the presidency. He was joined by the President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. He picked up the baton in creating a “new country” literally a few months after Mirziyoyev.

According to Radio Azatlyk, the slogan “New Kazakhstan” came about three years after Tokayev’s election as president and after the bloody January events in the oil-rich republic, which left Tokayev’s predecessor, Nursultan Nazarbayev, as a political outsider.

In the summer of 2023, the “baton of the new country” was picked up by the Head of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov. To do this, he issued a new presidential book – “The Path to Building a New Kyrgyzstan”, in which he shares the development strategy of the poor country.

Associate Professor of International Relations and Political Science at Near East University of Northern Cyprus Asel Tutumlu shared the observation that the strategies of the five former Soviet republics of Central Asia are surprisingly consistent.

Kyrgyzstan is the country that has seen the most leadership changes. There have already been six presidents, three of whom were removed from power. But Japarov, unlike Mirziyoyev and Tokayev, is not trying to convince everyone that the Kyrgyz live in a new country. On the contrary, he claims that the creation of a “new Kyrgyzstan” will take about 20-30 years.

However, it is also clear that President Japarov no longer embraces the Kyrgyz culture of street protests that brought opposition leader Japarov out of jail and into the presidency in less than two weeks in 2020.

The 2021 constitution, adopted by referendum, strengthened his position at the expense of parliament and removed a clause barring incumbent presidents from running for a second term. But it has also, in many ways, returned the political system to the one that existed during the authoritarian administration of second President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, under which Japarov headed the anti-corruption agency before the 2010 revolution.

Among his own achievements, which Japarov listed as Kyrgyzstan’s entry onto a new path, is the transfer of the Kumtor gold mine to the state. This fact increased the attractiveness of the new president even at the beginning of his presidential term. In addition, the fight against corruption schemes with the president’s allies, who ended up behind bars or were fired. But this fight is selective, since there is a lot of evidence when other dishonest figures who do not criticize the president go unpunished.

Emomali Rahmon and Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov continue to rule the countries of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. The latter, despite the fact that he allowed his son Serdar to take the chair of the head of state, continues to rule and influence the fate of the country. But in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the new rulers found it convenient to distance themselves from their predecessors, who became associated with all the bad things in the country. This usually happens when the need for change increases.

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, for example, called Kazakhstan “the only country in our vast region that has made such significant changes in its political system in such a short time.” But not everyone in the country agrees with this opinion.

Uzbekistan has a better claim to the country’s renewal plans, partly because of the very low bar set by the ultra-authoritarian administration of the first president, Islam Karimov, Mirziyoyev’s former boss.

Mirziyev’s first term brought much praise to the country, as his government tackled systematic forced labor, allowed some degree of freedom of speech and made the national currency fully convertible. But further reforms, which brought Uzbekistan the title of “country of the year” according to the Economist magazine in 2019, have since lost their momentum.

By launching constitutional reform campaigns, Central Asian leaders “want to help people understand the impact of change through their own branding,” said Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili, founding director of the Center for Governance and Markets at the University of Pittsburgh. But this is nothing more than a public limitation on one’s own power.